Nonlinear Solvers

Nonlinear Solvers with PETSc

At a Glance

| Questions | Objectives | Key Points |

| 1. What are the tradeoffs between exactness and inexactness in Newton methods? | Observe trade-offs between inner and outer iterations as linear solver tolerance is varied | An inexact linear solver may be less robust but can result in significantly faster nonlinear solver |

| 2. What makes a scalable inexact Newton method? | Observe execution time and convergence behavior as mesh spacing is decreased | Newton methods exhibit mesh independent convergence, but need to be combined with scalable linear solvers |

| 3. How and when do nonlinear solvers fail? | Explore limits of nonlinear solvers by systematically increasinging problem nonlinearity | Nonlinear solvers can fail in a variety of ways, and some workarounds exist |

| 4. Can we improve the robustness of Newton’s method by combining it with other solvers? | Explore nonlinear preconditioning for highly nonlinear problems | Nonlinear analogs of ideas from iterative linear solvers can significantly improve nonlinear solvers |

Note: The executable for this lesson should be provided, but if it needs to be rebuilt do

cd track-5-numerical/nonlinear_solvers_petsc

make ex19

Introduction

Systems of nonlinear equations \[F(x) = b \quad \mathrm{where} \quad F : \mathbb{R}^N \to \mathbb{R}^N\]

arise in countless settings in computational science. Unlike their linear counterparts, direct methods for general nonlinear systems do not exist. Iterative methods are required!

In this lesson, we will do some hands-on exploration, solving a model nonlinear problem using the nonlinear solvers from the PETSc library. We will focus on variants on Newton’s method, exploring exact vs. inexact Newton methods, Newton-Krylov, and Newton-Krylov-multigrid methods. We will end with some exploration of a topic that is relatively unexplored both theoretically and experimentally: nonlinear preconditioning.

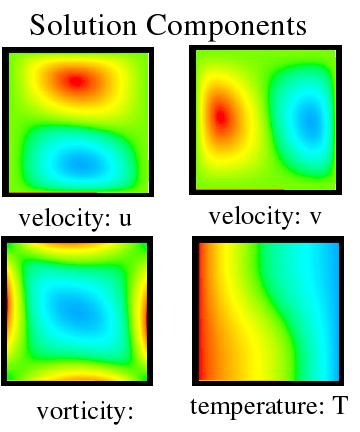

The Problem We Are Solving: the driven cavity CFD benchmark

We will use the nonlinear solvers provided by the PETSc Scalable Nonlinear Equation Solvers

(SNES) component to solve the steady-state nonisothermal driven cavity problem as implemented

in SNES example ex19.

This is a classic CFD benchmark that simulates a fluid-filled 2D box with a lid that moves at

constant tangential velocity (probably employing a conveyor belt).

Flow is driven by both the lid motion and buoyancy effects.

Our example uses a velocity-vorticity formulation, in which the governing equations can

be expressed as

\[\begin{align*}

- \Delta U - \partial_y \Omega &= 0 \\

- \Delta V + \partial_x \Omega &= 0 \\

- \Delta \Omega + \nabla \cdot ([U \Omega, V \Omega]) - \mathrm{Gr}\ \partial_x T &= 0 \\

- \Delta T + \mathrm{Pr}\ \nabla \cdot ([U T, V T]) &= 0

\end{align*}\]

where \(U\) and \(V\) are velocities, \(T\) is temperature, \(\Omega\) is vorticity, \(\mathrm{Gr}\) is the Grashof number and \(\mathrm{Pr}\) is the Prandtl number.

Example 1: Initial exploration and understanding PETSc options

Let’s begin by running the ex19 on a single MPI rank with some basic command line options.

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -snes_monitor -snes_converged_reason -da_grid_x 16 -da_grid_y 16 -da_refine 2 -lidvelocity 100 -grashof 1e2

You should see output similar to

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 100.

0 SNES Function norm 7.681163231938e+02

1 SNES Function norm 6.582880149343e+02

2 SNES Function norm 5.294044874550e+02

3 SNES Function norm 3.775102116141e+02

4 SNES Function norm 3.047226778615e+02

5 SNES Function norm 2.599983722908e+00

6 SNES Function norm 9.427314747057e-03

7 SNES Function norm 5.212213461756e-08

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 7

Number of SNES iterations = 7

The table below explains the options we have used:

| Option Flag | Effect |

-snes_monitor

| Show progress of the SNES solver |

-snes_converged_reason

| Print reason for SNES convergence or divergence |

-da_grid_x 16

| Set initial grid points in x direction to 16 |

-da_grid_y 16

| Set initial grid poings in y direction to 16 |

-da_refine 2

| Refine the initial grid 2 times before creation |

-lidvelocity 100

| Set dimensionless velocity of lid to 100 |

-grashof 1e2

| Set Grashof number to 1e2 |

An element of the PETSc design philosphy is extensive runtime customizability.

We can always use -help to enumerate and explain the various command-line options

available to a PETsc executable.

(Note that the help will be tailored to according to the set of options being specified.)

To see the details of how our SNES solver is configured, we can add -snes_view, which will

print information at the end of the run about the SNES object and the underlying KSP

(linear solvers) and PC (preconditioners) objects.

Example -snes_view output

-snes_view outputNonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 7

SNES Object: 1 MPI processes

type: newtonls

maximum iterations=50, maximum function evaluations=10000

tolerances: relative=1e-08, absolute=1e-50, solution=1e-08

total number of linear solver iterations=835

total number of function evaluations=11

norm schedule ALWAYS

Jacobian is built using colored finite differences on a DMDA

SNESLineSearch Object: 1 MPI processes

type: bt

interpolation: cubic

alpha=1.000000e-04

maxstep=1.000000e+08, minlambda=1.000000e-12

tolerances: relative=1.000000e-08, absolute=1.000000e-15, lambda=1.000000e-08

maximum iterations=40

KSP Object: 1 MPI processes

type: gmres

restart=30, using Classical (unmodified) Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization with no iterative refinement

happy breakdown tolerance 1e-30

maximum iterations=10000, initial guess is zero

tolerances: relative=1e-05, absolute=1e-50, divergence=10000.

left preconditioning

using PRECONDITIONED norm type for convergence test

PC Object: 1 MPI processes

type: ilu

out-of-place factorization

0 levels of fill

tolerance for zero pivot 2.22045e-14

matrix ordering: natural

factor fill ratio given 1., needed 1.

Factored matrix follows:

Mat Object: 1 MPI processes

type: seqaij

rows=14884, cols=14884, bs=4

package used to perform factorization: petsc

total: nonzeros=293776, allocated nonzeros=293776

total number of mallocs used during MatSetValues calls=0

using I-node routines: found 3721 nodes, limit used is 5

linear system matrix = precond matrix:

Mat Object: 1 MPI processes

type: seqaij

rows=14884, cols=14884, bs=4

total: nonzeros=293776, allocated nonzeros=293776

total number of mallocs used during MatSetValues calls=0

using I-node routines: found 3721 nodes, limit used is 5

Managing PETSc Options

PETSc offers a very large number of runtime options. All can be set via command line, but can also be set from input files and shell environment variables.

To facilitate readability, we’ll put the command-line arguments common to the remaining

hands-on exercises in the PETSC_OPTIONS environment variable.

export PETSC_OPTIONS="-snes_monitor -snes_converged_reason -lidvelocity 100 -da_grid_x 16 -da_grid_y 16 -ksp_converged_reason -log_view :log.txt"

We’ve added -ksp_converged_reason to see how and when linear solver halts.

We’ve also added -log_view to write the PETSc performance logging info to a file, log.txt.

Such performance logs are full of useful information for understanding the performance of

a PETSc code, but we don’t have time to explore them in this session.

(For those interested, see Chapter 13, “Profiling”, of the

PETSc User Manual.)

Here, we will simply use the performance logs to find the overall wall-clock time via,

which we can quickly find by using the grep utility:

grep Time\ \(sec\): log.txt

(The first number returned is the total run time in seconds.)

IMPORTANT: When you finish these hands-on lessons, be sure to clear your PETSC_OPTIONS environment variable

(do “unset PETSC_OPTIONS”) if you will be doing hands-on exercises in another session.

Otherwise, you may get unexpected behavior if running executables that are linked against PETSc.

Example 2: Exact vs. Inexact Newton

The output from running -snes_view in the previous exercise shows us that PETSc defaults

to an inexact Newton method. To run with exact Newton (and to check the execution time), we

use -pc_type lu, which indicates to the KSP object (which controls the linear solver) that

the underlying preconditioner should be an full LU decomposition:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e2 -pc_type lu

grep Time\ \(sec\): log.txt

(Remember, the above command assumes that you have set PETSC_OPTIONS as specified in the

preceding section.)

Sample output on my laptop (Dell XPS 13 with Intel Core i7-10710U CPU)

rmills@encke:~/proj/petsc/src/snes/tutorials (master=)$ mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e2 -pc_type lu

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 100.

0 SNES Function norm 7.681163231938e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

1 SNES Function norm 6.581690463182e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

2 SNES Function norm 5.291809327801e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

3 SNES Function norm 3.772079270664e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

4 SNES Function norm 3.040001036822e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

5 SNES Function norm 2.518761157519e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

6 SNES Function norm 9.230363584762e-03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

7 SNES Function norm 6.155757710494e-09

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 7

Number of SNES iterations = 7

rmills@encke:~/proj/petsc/src/snes/tutorials (master=)$ grep Time\ \(sec\): log.txt

Time (sec): 6.728e-01 1.000 6.728e-01

The work required to solve the inner, linear interation so precisely is likely wasted. Let’s try using the default iterative solver with some different tolerances. Start with

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e2 -ksp_rtol 1e-8

and then try some larger values for relative convergence tolerance, -ksp_rtol.

Try -ksp_rtol 1e-5 (the PETSc default) next, and try increasing it by an order of

magnitude each time.

What happens to the SNES iteration count? When does the SNES solve diverge?

The SNES iteration count is 7 initially, then increases to 8 at a relative tolerance of 1e-3 for the linear solver, and then 10 at a tolerance of 1e-2. The SNES solve diverges when run with a linear solver tolerance of 1e-1.

What yields the shortest execution time?

On my laptop, the loosest tolerance I tried, -ksp_rtol 1e-2, turns out to be fastest, able

to solve the problem in 0.43 seconds. Though it requires more Newton iterations, it performs

far fewer linear solver iterations. Running with the default tolerance of 1e-5 requires

0.60 seconds. A tolerance of 1e-8 is far too high, resulting in many linear solver iterations

and an execution time of over 1.2 seconds.

Using LU factorization turns out to not be too bad for this small problem (around 0.68

seconds), but it is difficult for LU to scale up to large problems.

Example 3: Scaling up the grid size and running in parallel

Let’s explore what happens as we scale up the grid size for our model problem.

For this exercise, we will run in parallel because experiments may take too long otherwise.

We will use a fixed number of MPI ranks, even though this number is really too large for

the smaller grids, to eliminate effects due to varying the size of the domains used by the

default parallel preconditioner (block Jacobi with ILU(0) applied on each block).

We also use BiCGStab (-ksp_type bcgs) instead of the default linear solver, GMRES(30), which

will fail for some cases.

Using the linear solver defaults, increase the size of the grid (that is, decrease the grid spacing) and observe what happens to iteration counts and execution times:

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -da_refine 2

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -da_refine 3

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -da_refine 4

Sample output for -da_refine 4 case

-da_refine 4 case$ mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -da_refine 4

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 100.

0 SNES Function norm 1.545962539057e+03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 125

1 SNES Function norm 9.782056791818e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 128

2 SNES Function norm 6.621936395441e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 389

3 SNES Function norm 3.155672307430e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 470

4 SNES Function norm 8.129969608884e-03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 425

5 SNES Function norm 8.852310456001e-08

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 5

You should observe that the Newton solver shows “mesh independence” – that is, as we refine the grid spacing, we see roughly the same convergence behavior for the Newton iterates. This is not true, however, for the linear solver, which shows unsustainable growth in the number of iterations it requires.

What happens if we employ a Newton-Krylov-multigrid method?

Add -pc_type mg to use a geometric multigrid preconditioner (defaults to a V-cycle, but

check out the -help output to see how to use other types; you may also want to try

-snes_view to see the multigrid hierarchy):

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -pc_type mg -da_refine 2

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -pc_type mg -da_refine 3

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -pc_type mg -da_refine 4

Sample output for -pc_type mg -da_refine 4 case

-pc_type mg -da_refine 4 casempiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -ksp_type bcgs -grashof 1e2 -pc_type mg -da_refine 4

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 100.

0 SNES Function norm 1.545962539057e+03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 6

1 SNES Function norm 9.778196290981e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 6

2 SNES Function norm 6.609659458090e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 7

3 SNES Function norm 2.791922927549e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 6

4 SNES Function norm 4.973591997243e-03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 6

5 SNES Function norm 3.241555827567e-05

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 9

6 SNES Function norm 9.883136583477e-10

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 6

The takeaway here is that the combination of the fast convergence of a globalized Newton method and a multigrid preconditioner for the inner, linear solve can be a powerful and highly scalable solver.

Example 4: Increasing the strength of the nonlinearity

Let’s explore what happens as we increase the strength of the nonlinearity by raising the Grashof number. Try running

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e2

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e3

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e4

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4

Sample output for mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 13000.

0 SNES Function norm 7.971152173639e+02

Linear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_ITS iterations 10000

Nonlinear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_LINEAR_SOLVE iterations 0

Oops! At a Grashof number of 1.3e4, we get a failure in the linear solver. Let’s see if a stronger preconditioner can help us:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4 -pc_type mg

Sample output for mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4 -pc_type mg

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4 -pc_type mgmpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3e4 -pc_type mg

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 13000.

...

4 SNES Function norm 3.209967262833e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 9

5 SNES Function norm 2.121900163587e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 9

6 SNES Function norm 1.139162432910e+01

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

7 SNES Function norm 4.048269317796e-01

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

8 SNES Function norm 3.264993685206e-04

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

9 SNES Function norm 1.154893029612e-08

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 9

Success! But what if we increase the Grashof number a little more? Try

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type mg

Sample output for mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type mg

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type mglid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 13373.

...

48 SNES Function norm 3.124919801005e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 17

49 SNES Function norm 3.124919800338e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 17

50 SNES Function norm 3.124919799645e+02

Nonlinear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_MAX_IT iterations 50

No good! Let’s try brute force and employ -pc_type lu:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type lu

Sample output for mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type lu

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type lumpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -pc_type lu

...

48 SNES Function norm 3.193724239842e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

49 SNES Function norm 3.193724232621e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

50 SNES Function norm 3.193724181714e+02

Nonlinear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_MAX_IT iterations 50

We eventually reach a point that seems to be beyond the capabilities of our Newton solver. What now?

Example 5: Nonlinear Richardson Preconditioned with Newton

Since our Newton solver is unable to make progress on its own, let’s try combining it with another nonlinear solver. We will try nonlinear Richardson iteration, preconditioned with Newton’s method:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_type newtonls -npc_snes_max_it 4 -npc_pc_type mg

Sample output

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 13373.

Nonlinear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_INNER iterations 0

Number of SNES iterations = 0

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.3373e4 -snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_type newtonls -npc_snes_max_it 4 -npc_pc_type lu

Sample output

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 13373.

0 SNES Function norm 7.987708558131e+02

1 SNES Function norm 8.467169687854e+02

2 SNES Function norm 7.300096001529e+02

3 SNES Function norm 5.587232361127e+02

4 SNES Function norm 3.071143076019e+03

5 SNES Function norm 3.347748537471e+02

6 SNES Function norm 1.383297972324e+01

7 SNES Function norm 1.209841384629e-02

8 SNES Function norm 8.660606193428e-09

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 8

So nonlinear Richardson preconditioned with Newton has managed to get us further than Newton alone. Let’s try increasing the Grashof number a little more:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_type newtonls -npc_snes_max_it 4 -npc_pc_type lu

Sample output

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 14000.

...

37 SNES Function norm 5.992348444448e+02

38 SNES Function norm 5.992348444290e+02

Nonlinear solve did not converge due to DIVERGED_INNER iterations 38

We’ve hit another barrier. What about switching things up? Let’s try preconditioning Newton with nonlinear Richardson.

Example 6: Newton Preconditioned with Nonlinear Richardson

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 1 -snes_max_it 1000

Sample output

...

352 SNES Function norm 2.145588832260e-02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 7

353 SNES Function norm 1.288292314235e-05

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

354 SNES Function norm 3.219155715396e-10

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 354

Well, this did eventually work, but it’s pretty slow. Why don’t we try upping the number of iterations of the inner, nonlinear Richardson solver?

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 3

Sample output

...

23 SNES Function norm 4.796734188970e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 7

24 SNES Function norm 2.083806106198e-01

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

25 SNES Function norm 1.368771861149e-04

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

26 SNES Function norm 1.065794992653e-08

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 26

Much improved! Can we do even better?

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 4

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 5

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 6

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1.4e4 -pc_type mg -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 7

Sample output

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 14000.

0 SNES Function norm 8.016512665033e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 11

1 SNES Function norm 7.961475922316e+03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 10

2 SNES Function norm 3.238304139699e+03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 10

3 SNES Function norm 4.425107973263e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 9

4 SNES Function norm 2.010474128858e+02

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

5 SNES Function norm 2.936958163548e+01

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

6 SNES Function norm 1.183847022611e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 8

7 SNES Function norm 6.662829301594e-03

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 7

8 SNES Function norm 6.170083332176e-07

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 8

Newton preconditioned with nonlinear Richardson can be pushed quite far! Try

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 2 -grashof 1e6 -pc_type lu -npc_snes_type nrichardson -npc_snes_max_it 7 -snes_max_it 1000

Sample output

lid velocity = 100., prandtl # = 1., grashof # = 1e+06

...

69 SNES Function norm 4.241700887134e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

70 SNES Function norm 3.238739735055e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

71 SNES Function norm 1.781881532852e+00

Linear solve converged due to CONVERGED_RTOL iterations 1

72 SNES Function norm 1.677710773493e-05

Nonlinear solve converged due to CONVERGED_FNORM_RELATIVE iterations 72

Wow! The solver converges with a Grashof number of one million. If you want to explore further, see how much further you can push this!

Take-Away Messages

PETSc provides a wide assortment of nonlinear solvers through the SNES component.

With it, users can build sophisticated solvers from composable algorithmic components:

- Inner, linear solves can employ full range of solvers and preconditioners provided by PETSc

KSPandPC- Multigrid solvers particularly important for mesh size-independent convergence

- Composite nonlinear solvers can be built analogously, using building blocks from PETSc

SNES

Newton-Krylov methods are predominant, but there is a large design space of “composed” nonlinear solvers to explore:

- Not well-explored theoretically or experimentally (interesting research opportunities!)

- Composed nonlinear solvers can be very powerful, though frustratingly fragile *As a rule of thumb, nonlinear Richardson, Gauss-Seidel, or NGMRES with Newton often improves robustness

Further items to explore include

- Nonlinear domain decomposition (

SNESASPIN/SNESNASM) and nonlinear multigrid (or Full Approximation Scheme,SNESFAS) methods - PETSc timesteppers use

SNESto solve nonlinear problems at each time step- Pseudo-transient continuation (

TSPSEUDO) can solve highly nonlinear steady-state problems

- Pseudo-transient continuation (

Extra Credit: Running Nonlinear Solvers Using PETSc’s GPU Back-Ends

The concepts we have covered so far are mostly orthogonal to the topic of how to run PETSc solvers on GPUs. Since computing on GPUs has become so important, however, we suggest a few exercises here for students who want a brief look at GPU support in PETSc and how its nonlinear solvers can be executed on GPUs.

Before we begin, let’s clear the PETSC_OPTIONS environment variable were were using:

unset PETSC_OPTIONS

We will run a large version (-dm_refine 9) of the driven cavity problem, using multigrid with GPU and SIMD-friendly Chebyshev-Jacobi smoothing (-mg_levels_pc_type jacobi), and collect a breakdown by multigrid level (-pc_mg_log), logging performance in a text file.

We get the best CPU-only performance on ThetaGPU using 8 MPI ranks:

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -da_refine 9 -pc_type mg -mg_levels_pc_type jacobi -pc_mg_log -log_view :log_mg_cpu_n8.txt

Running on GPU, we get best performance using only one rank (we could probably use more if running NVIDIA MPS, but this is not enabled on ThetaGPU):

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 9 -pc_type mg -mg_levels_pc_type jacobi -pc_mg_log -dm_vec_type cuda -dm_mat_type aijcusparse -log_view_gpu_time -log_view :log_mg_gpu_n1.txt

(The -log_view_gpu_time option is actually not needed in the 3.17 release of PETSc,

but in future releases it will be required to get full timings for all events on the

GPU. This change is being added because of the overhead associated with collecting these timings.)

Opening up the .txt versions of the -log_view files will show us a lot of data about the performance.

There is a useful overall summary at the top, and then timings for many “events”, which occur during

different “stages” of the computation.

When PETSc has been built with GPU support, several additional columns, showing copies between CPU and

GPU memory and the percentage of flops computed on the GPU, are present.

The events that are logged are not exclusive:

The SNESSolve time is that required to solve our entire problem.

But the time for other events, such as KSPSolve (invoked in solving the Jacobian system inside the Newton solve),

are included in the SNESSolve time.

It can be difficult to tell from the text output how the logging events are nested. So let’s repeat the same runs, but this time generate stack trace files that can be used to generate flame graphs.

On 8 MPI ranks for CPU-only:

mpiexec -n 8 ./ex19 -da_refine 9 -pc_type mg -mg_levels_pc_type jacobi -pc_mg_log -log_view :log_mg_cpu_n8.stack:ascii_flamegraph

And on 1 MPI rank for the GPU case:

mpiexec -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 9 -pc_type mg -mg_levels_pc_type jacobi -pc_mg_log -dm_vec_type cuda -dm_mat_type aijcusparse -log_view_gpu_time -log_view :log_mg_gpu_n1.stack:ascii_flamegraph

Download the .stack files to your local machine, and then use SpeedScope.app to generate interactive flame graphs of the performance data, which will let you examine the hierarchy of PETSc events and their relative costs.

One thing to note is the relative distribution of time in MGSmooth events (part of PCApply).

These are the application of the smoother on a multigrid level; MGSmooth Level 0 corresponds

to the smoother application on the coarsest level of the multigrid hierarchy.

See how the smoother application on coarse levels all take roughly the same time on the GPU?

This points to the high kernel launch latency. What other noteworthy differences can you find?

Additional Things To Try

Look at sources of speedup (or slowdown!) for the GPU vs. CPU

The total time in SNESSolve tells us the time required to solve our entire problem.

Compare these for the CPU and GPU cases to get the overall speedup, but what parts

sped up in the GPU case? Which parts actually slowed down?

(The slowdowns are mostly due to the fact that the nonlinear function and Jacobian routines in

SNES ex19 do not run on the GPU—verify this by looking at the GPU %F column in the

text version of the log—and we had to use fewer ranks in this case. See

SNES tutorial ex55 in the main development branch of PETSc for an example where

these run on the GPU.)

Running with a different GPU back-end

If you’d like to try another GPU-back end, you can try PETSc’s Kokkos/Kokkos Kernels one.

Run with -dm_mat_type aijkokkos -dm_vec_type kokkos:

mpirun -n 1 ./ex19 -da_refine 9 -pc_type mg -mg_levels_pc_type jacobi -pc_mg_log -dm_vec_type kokkos -dm_mat_type aijkokkos -log_view_gpu_time -log_view :log_mg_kokkos_n1.txt

Experimenting with different multigrid cycle types

Our SNES ex19 runs defaulted to using multigrid V-cycles.

Try running with W-cycles instead by using the option -pc_mg_cycle_type w.

Unlike V-cycles, W-cycles visit coarse levels many more times than fine ones. What does this do to the time spent in multigrid smoothers for the GPU case vs. the CPU-only one? Should one or the other of these be favored when using GPUs?

An Important Reminder About Cleaning Up Your PETSc Options

IMPORTANT: If you will be doing hands-on lessons from other ATPESC sessions, remember to clear your PETSC_OPTIONS environment variable:

unset PETSC_OPTIONS

Otherwise, you may get unexpected behavior from executables that link against PETSc.

Further Reading

- PETSc manual

- PETSc/TAO website

- Composing Scalable Nonlinear Algebraic Solvers

- Toward Performance-Portable PETSc for GPU-based Exascale Systems